What does it take to make technology helpful in healthcare?

UnityAI aims to bring a "system of action" into hospital operations

Origin story

In 2018, I began working as a data scientist for a division of the largest private hospital operator in the United States. It was my first job in healthcare, so I was reading everything I could find to get up to speed on the state of play for bringing intelligent systems into hospital settings. A couple of months into that role, I read an article in The New Yorker that has troubled me ever since; the article is “Why doctors hate their computers” by Atul Gawande.

Gawande frames the essay by writing of his personal experience onboarding to a new electronic health record (EHR) system. He talks about his early optimism that he would go through the learning curve and come out the other side with increased ability to be effective in his practice. That cheery perspective gives way to something akin to professional despair: “Three years later I’ve come to feel that a system that promised to increase my mastery over my work has, instead, increased my work’s mastery over me . . . . somehow we’ve reached a point where people in the medical profession actively, viscerally, volubly hate their computers.”

During the next five years, I tried to keep Gawande’s words front of mind as I built technology for hospital-based frontline caregivers and managers. I had a chance to see first-hand what worked (building with rapid-cycle feedback from actual users) and what didn’t work (building with a mile-long requirements document that was dreamed up in a conference room eighteen months ago). I experienced the satisfaction of bringing tools into hospitals that were heavily relied on during the peak of the COVID pandemic. The highest praise is a nurse telling you that they can get through their day a little easier because of something you helped create for them.

UnityAI

Edmund Jackson, Cody Hall, and I founded UnityAI earlier this year because hospital operations need to level up, and we believe that intelligent automation, generative AI, and other modern techniques represent the best opportunity for that improvement to happen.

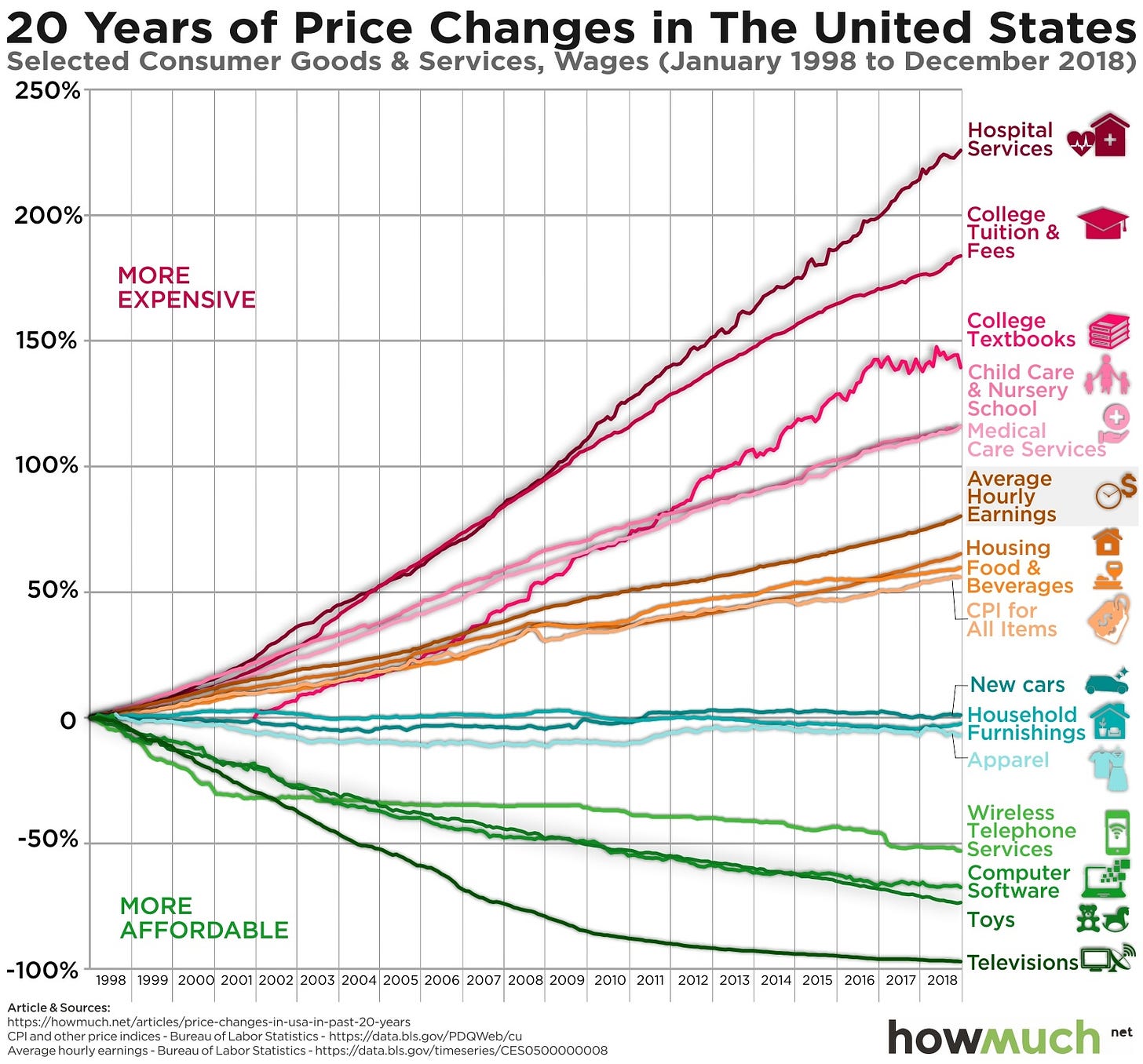

Over the last fifty years, most industries have experienced significant productivity and efficiency gains by incorporating technology and automation. Healthcare—along with higher education and the performing arts—has been an outlier to that trend. There are plenty of reasons why this is the case; the simplest is the Baumol Effect. To summarize in simplest terms: industries like healthcare experience a rise in wages that keeps pace with the broader economy but do not demonstrate an accompanying rise in productivity. The consequence is a more rapid rise in cost for services rendered.

Why has healthcare been an outlier to the trend of technology and automation leading to greater productivity and cost efficiency? UnityAI has a very clear point of view on this question: EHRs (and other systems that have developed in the ecosystem around them) are primarily concerned with storing patient records and making them accessible for lookup, quality reporting, and billing purposes. Doctors can place orders, and nurses can look up those orders to determine the right steps, but there is essentially zero distinction between an order that takes five minutes to fulfill and an order that involves twenty steps that will be spread over multiple days. In other words, there is no “system of action” that specifies, orchestrates, and coordinates the actions that caregivers take to provide the best care for patients; that work remains fully in the heads and hands of clinicians … and current systems generally add to that burden.

So that’s why we created UnityAI. We want to create an intelligent system of action that can help caregivers do the work itself. We want to design a great user experience that minimizes cognitive load on the user and enables them to easily find what they need so they can focus on the patient. We want to place caregivers fully in control of determining what the system prioritizes (i.e., what it considers the “best thing” to do in a given situation) and then let the system handle the grunt work of actually executing those tasks. We want to remove screens from standing between you and your nurse or doctor.

We don’t want doctors and nurses to hate their computers. We don’t want them to love their computers, either. We want clinicians to forget that the computers are there at all, because the system blends seamlessly into their day-to-day work and is just another tool in their very capable hands.